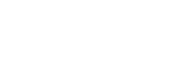

Poet Warrior

by Joy Harjo

W.W. Norton, 2021

Hardcover: $25.00

Genre: Nonfiction; Memoir

Review by Pam Kingsbury

Joy Harjo’s Poet Warrior is a graduate course in what it means to find healing through poetry, as well as to live as a compassionate human.

Describing herself as “being equally left and right-brained,” Joy Harjo has made her life’s work as a writer and a teacher, as well as a daughter, mother, grandmother, and now matriarch, taking up the ideals of poetic justice, crazy bravery, and what it means to be a poet warrior. Her beliefs that “we are all here to serve each other” and “poet is synonymous with truth” have become more pronounced with each successive project. The first Native Poet Laureate of the United States and the second poet (after Robert Pinsky) to hold the office three times embraces with more confidence her roles as poet, artist, mystic, and prophetess in her second memoir.

Acknowledging that “I have told some of these stories many times,” Harjo writes about the lessons of the heart (love, grief, letting go), the act of forgiveness, and the understanding that generational wounds (traced back to Monahwee) need to be healed. Poet Warrior, written during the most intense phase of the recent quarantine, delves into the intersection of poetry and storytelling as healing arts, the individual’s duty to examine the state of her country, and the current state of the planet.

Both Harjo’s first memoir, Crazy Brave (the English translation of her family name from Mvskoke), and Poet Warrior offer a long view of history and kind views of humanity. In Poet Warrior, which is divided into six sections – Ancestral Roots, Becoming, A Postcolonial Tale, Diamond Light, Teachers, and Sunset – Harjo moves between prose, song, and poetry gracefully and artfully through her experiences. Her use of the personae of the girl warrior becoming the poetic warrior ties the poems to the traditional prayers and chants of the Mvskoke while serving as measures of the transitions in her life.

Harjo’s credit to her teachers – and she believes we are all teachers – is one of the most heartfelt threads in Poet Warrior.

She attributes her love for storytelling to her extended family – aunts, uncles, cousins, and the elders. As a child she loved being told the same stories over and over, as well as learning new words. She would hide under the kitchen table and listen to her mother (who “was a talker”) and her mother’s friends’ conversations and laughter. Her love for words (‘word finding”) would cause one of her first shameful moments when she, like most children, repeated a word her father had used casually but felt was unsuitable for children. Her father’s anger and a lost tooth silenced her impulse to talk for many years. Discovering poetry offered her solace as she was subsumed by its rhythms and song. She memorized William Blake’s “The Lamb” and asked for a book of poetry for her birthday (she was given Louis Untermeyer’s Golden Treasury of Poetry), which she read aloud to herself. “I retreated to poetry. I disappeared into the music. Poetry lingered with me.”

She describes trying to keep her father from hurting her mother and her own attempt to hold him back as her “first act of justice.” She learns from loving each parent as much as the other the contradictions of the “genealogy of rage,” the “genealogy of justice,” and the need to speak her truths.

In one of the kindest and most forgiving passages (which does not mean forgetting) in the book, she concedes that her stepfather (referred to as “the monster” for his emotional and physical abuse) was one of her greatest teachers. Avoiding him helped shape her house of imagination.

Her formal education included attending the Institute for American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she formed lifelong bonds and her “collective family with other student artists,” and where she started to find her place as an artist. While working as an attendant at St. Vincent Hospital in Santa Fe, she discovered a talent for healing and was awarded a scholarship to attend the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. There, she would become part of the Native American Renaissance and the emerging Native Rights Movement.

Harjo’s trajectory between the memories of her ancestors (with their roots in Alabama), her ancestors’ stories on the Trail of Tears (“the long walk”), and her own travels (starting with leaving Oklahoma at fourteen and returning to Oklahoma in her sixties), serves as an education to readers by offering an oral and tribal history of the connections between the two states.

Joy Harjo has always striven to be a truth-teller, and she does not flinch at the ugly truths. Instead she brings them to light “to build a house of knowledge.” Poet Warrior is a powerful memoir rooted in the understanding that words and remembrance have the power to heal.

Pam Kingsbury, who teaches at the University of North Alabama, is the author of Inner Voices, Inner Views.