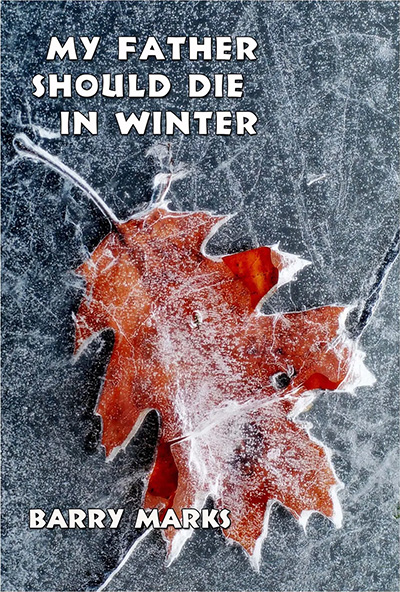

My Father Should Die in Winter

By Barry Marks

Brick Road Poetry Press, 2021

Paperback: $15.95

Genre: Poetry

Reviewed by Edward Journey

My Father Should Die in Winter, a new book of poetry by Barry Marks, is a work of grief, transcendence, enduring memory, and memory lost. The reader gathers morsels of information in the book’s progression after an opening page that simply lists names and dates for three individuals – Asher, Leah, and Noah. A blurb on the jacket informs us that Asher is Barry Marks’s father, who died in 2017 “after a long, debilitating illness.” Leah is the author’s teenaged daughter, whose life “was ended by a drunk driver in 2007.” Noah, born the year Leah died, is his son. Knowledge of these things is not essential to appreciating the poetry, but it adds depth to understanding the motivation for the plaintive and longing tone.

In addition to being a writer, Barry Marks is a Birmingham attorney. His previous books include Possible Crocodiles and Sounding. A two-part poetry/music collaboration with University of Montevallo professor Alan Goldspiel includes and Sons, a companion piece to My Father Should Die in Winter. Marks was Alabama’s 1999 “Poet of the Year” and has served as president of the Alabama State Poetry Society.

The opening poem of My Father Should Die in Winter gives the book its title and addresses the reticence of a father, along with the son’s belief that a well-chosen word “would warm / the air between us.” He later realizes that his best words are “like leaves too strong / to fall until the last wind. // They will be trapped / all winter / in prisons of ice, / staring at the sun.” From such a beginning, images of ice and winter recur frequently in poems of subdued grief and mourning in which the vitality of the language cushions the themes of loss.

Another early poem, “Castello di Postignano,” evokes a need to communicate to a lost one who has gone forever. “I will write you / though I cannot write you / back into this world” is the lament for a girl – “The Girl,” we read later, “who loved Night.”

The lyric poetry of My Father Should Die in Winter alternates with a series of prose poems entitled “Buck Creek” – each attached to a season and year spanning from “Winter, 1937” to “Winter, 2017.” The “Buck Creek” series highlights the life of a boy, from a bear attack in his youth to the poetical “truth” he achieves at the end of his life. In an “Author’s Note” at the end, the reader learns that “Many of the poems in this book, and especially the ‘Buck Creek’ poems were written to be read aloud.” This reader had discovered that trait of the book long before I got to the end-note.

A powerful cycle of poems, “To the Third and Fourth Generation,” is inspired by Exodus 20:5. That’s the verse about a “jealous God” punishing the children for the sins of the fathers. The first section of the cycle begins, simply, “men hide.” The remaining six sections explore the meanings of being a man, presented as lessons to a son. “men who fear heights stay off tall buildings,” Marks writes, “not because they are afraid they will fall / because they are afraid they will jump.”

“Let Me Show You What Every Boy Should Know about His Gran’pa’s Timex” explains all of the workings of a watch to a son before a visit to a father-grandfather suffering from dementia, in the hope that the watch might elicit a reaction from the older man. The father lists various watch upgrades, explaining to the son that “those are called complications. / This will mean more to you / when I am winding down.”

In writing of his grief and questions after profound loss, Marks has created a document of truth and yearning that memorializes what it means to be human and alive. In “Buck Creek Fall, 1944,” a boy, who has just watched his father’s burial, envisions the life ahead of him, realizing that “He would live because that is what need be done.” In My Father Should Die in Winter, Barry Marks remembers lost loved ones by documenting their existence – “because everything is as real,” he writes, “as it is remembered.”

Edward Journey, a retired educator and theatre artist, is on the editorial board of Southern Theatre magazine, regularly shares his essays in the online journal “Professional Southerner” (www.professionalsoutherner.com), and has most recently published reviews, papers, and articles in Alabama Writers’ Forum, Arkansas Review, Southern Theatre, and Theatre Symposium.