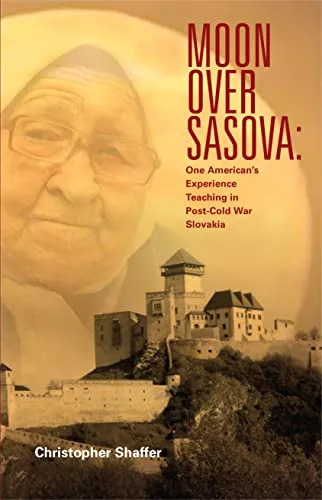

Moon over Sasova: One American’s Experience Teaching in Post-Cold War Slovakia

By Christopher Shaffer

Hellgate Press, 2021

Paperback: $12.95

Genre: Nonfiction; Memoir

Reviewed by Edward Journey

Since I embrace the concept of “serendipity,” I felt like I had encountered a kindred soul when I read the first sentence of Christopher Shaffer’s engrossing Moon over Sasova: One American’s Experience Teaching in Post-Cold War Slovakia. Shaffer writes, “I owe my Slovakia experience largely to serendipity.” That experience began when Shaffer, an undergraduate at Auburn University, spent the summer of 1991 in Mannheim, Germany, for a study abroad program. Admitting that his plan was “to study some, but travel more,” the summer became a transformative experience for the undergraduate abroad. A visit to Prague dispels his “grey and drab” illusion of what the former Soviet Eastern Bloc was like. His lushly entertaining descriptions of Prague and its abundance of Dixieland jazz bands make me want to visit, see, and hear those sights and sounds for myself. We are fortunate to have the opportunity to live the experience vicariously through Shaffer’s detailed and incisive memories.

Since I embrace the concept of “serendipity,” I felt like I had encountered a kindred soul when I read the first sentence of Christopher Shaffer’s engrossing Moon over Sasova: One American’s Experience Teaching in Post-Cold War Slovakia. Shaffer writes, “I owe my Slovakia experience largely to serendipity.” That experience began when Shaffer, an undergraduate at Auburn University, spent the summer of 1991 in Mannheim, Germany, for a study abroad program. Admitting that his plan was “to study some, but travel more,” the summer became a transformative experience for the undergraduate abroad. A visit to Prague dispels his “grey and drab” illusion of what the former Soviet Eastern Bloc was like. His lushly entertaining descriptions of Prague and its abundance of Dixieland jazz bands make me want to visit, see, and hear those sights and sounds for myself. We are fortunate to have the opportunity to live the experience vicariously through Shaffer’s detailed and incisive memories.

Shaffer’s travels alter his world-view and make him eager to spend more time in the former Soviet Eastern Bloc in the wake of its newly independent status. His book brings to mind that Mark Twain literary chestnut that “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” Although the majority of the book deals with events that happened in 1993, Moon over Sasova attains immediacy in the context of current events in Ukraine.

Christopher Shaffer, the Dean of Library Services at Troy University, has travelled extensively; during two stints as a teacher in Slovakia in the 1990s, he learned first-hand of the history and challenges of that part of the world. His first immersive teaching experience in 1993 occurred in the immediate wake of the so-called “Velvet Divorce” when Czechoslovakia peacefully dissolved to form the independent nations of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Shaffer and his roommate, Merrill, were assigned to the city of Banska Bystrica, living in the Sasova neighborhood.

Reading Moon over Sasova often feels like listening to a friend with a very sharp memory recounting a distant youthful adventure. Pertinent history is included in a casual and inconspicuous way. Shaffer observes that when he and his American colleagues arrived in Slovakia, the place had not had significant contact with Westerners, especially “evil” Americans, from 1948 to 1989. What ensues is a friendly post-Cold War clash of cultures and occasionally naïve American perspectives.

Shaffer’s experiences frequently remind us that there was a time before global connectivity. At one comic point early in his Slovakian stay, young Shaffer discovers that his AT&T telephone credit card is not much help in calling the States in a Slovakian economy that was still cash-only and where telegrams were still a common mode of communication. He arrives at a “solution” by calling the U.S. from a post office, while the postal worker, a “babushka,” listens in. Communication was more of a challenge in the ‘90s than the instant contact we now take for granted, but also, perhaps, more meaningful and rewarding.

Shaffer seasons his perspectives with wry observations that make his memories fresh and entertaining. He states his theory that all American disco balls were boxed and sent to Slovakia at the end of the 1970s. “The ubiquitous disco ball could be found in almost every bar I went to over the next half year,” he writes. He would know; I lost track of the number of inebriated stumbles from place to place the author recounts after too much imbibing of Slovak hospitality. “It seemed like everyone in every bar we went to wanted to buy us a drink,” he writes. In a place that seems to have prolific drinking habits, Shaffer discovered that the local mindset did not count wine and beer as alcohol while a liter of beer costs considerably less than a liter of milk. He cites sobering health statistics which arise from the nation’s drinking culture.

Moon over Sasova offers Shaffer’s observations about cultural traits, finding similarities among national identities along with major differences. In 1993, remnants of Soviet domination still influenced Slovakian life and culture and Shaffer’s analysis is often astute and fresh. He addresses what he calls the “slog” of daily life as he observes the regimented access and lines at the local markets. “People slogged through the system in the same way they slogged through the slush produced by the Slovak winter … surviving the ordeal was enough.” He details the twenty-minute hassle of buying a Coke and reflects on American privilege. He addresses casual Slovakian bigotry, particularly against Jews and Roma people, while also describing the warmth, generosity, and hardy stoicism that define the general population.

Moon over Sasova provides vivid descriptions of bland, soulless tracts of multi-story Soviet-era apartment complexes, as well as picturesque vistas and mountain adventures. Shaffer is surprised when he realizes that his friend Maja has kept a Ziploc bag, washed it, hung it to dry, and used it repeatedly since he first brought it to her. He finds an unexpected connection to his home in the American South when he discovers the dominance of fried meats in the Slovakian diet.

Shaffer has returned to Slovakia – to teach and to visit – several times since 1993. He regrets that it would be difficult now for anyone to replicate the experiences he had in his first visit to the region. He regrets the regression into totalitarianism that now occupies some nations of that former Soviet bloc. His observations, however, inspire a hopeful, promising tone for the future of Slovakia. He believes that the Slovaks of today “are a far happier people than we are in the United States.” As a teacher, he finds the Slovakian education system to be more relaxed and effective than the current educational system in the United States, which he describes as “running in circles while trying to teach to meaningless objectives” and being “far too open to comparisons to its penal system.” He praises Slovakia’s new president, Zuzana Caputova, “a young and progressive leader who is a firm believer in liberal democracy.” All in all, Moon over Sasova provides a refreshing and vibrant narrative of a tumultuous time that seems long-ago, but has powerful resonance with the events of today.

Edward Journey, a retired educator and theatre artist, is on the editorial board of Southern Theatre magazine, regularly shares his essays in the online journal “Professional Southerner” (www.professionalsoutherner.com), and has most recently published reviews, papers, and articles in Alabama Writers’ Forum, Arkansas Review, Southern Theatre, and Theatre Symposium.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.